But what if the centre right party is committed, for ideological or other reasons, to economic policies that are quite far from the centre ground? To get elected, it needs to do two things. First, it needs to focus its campaigning away from these unpopular right wing economic policies. This is possible if the centre-right party has substantial support in the media, which it often does. Second, it needs to focus on more social issues, and try to attract socially conservative voters who may also have relatively left wing economic views. This inevitably moves it away from the centre on these social issues, unless it can successfully paint parties to the left as very liberal. I will call this the ‘culture war’ mechanism.

Simon Wren-Lewis Why the centre-right has helped cause the drift to the far right in Western democracies

Wait, what? How does moving away from the centre help a centre-right party win elections? That broke my brain. But I can construct a geometric argument how this could work.

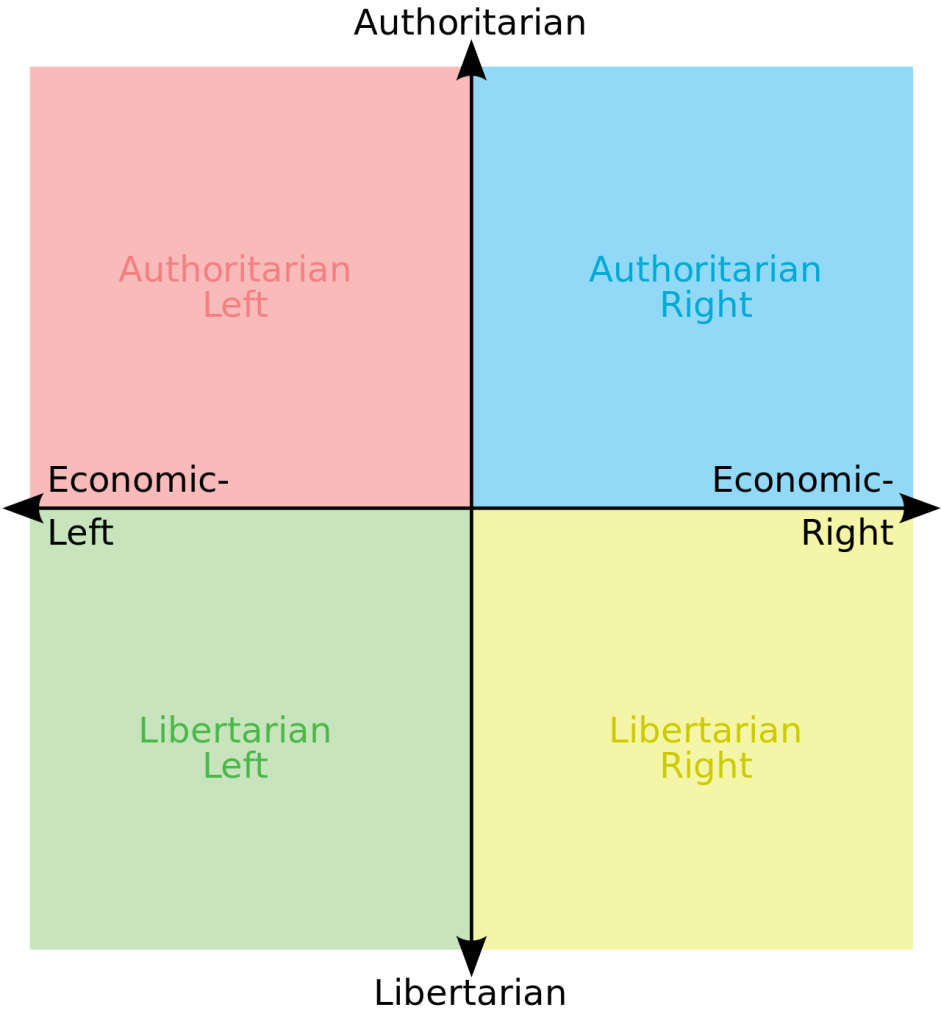

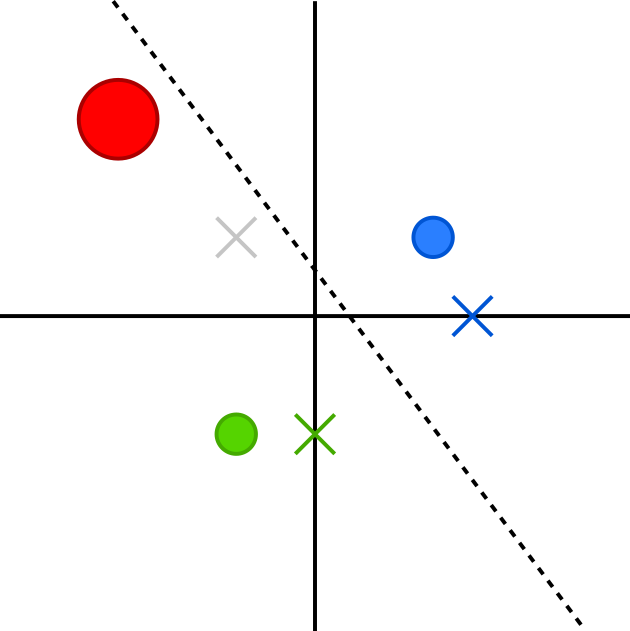

Start with the standard political compass. Even though this has been over-used and memeified enough to lose all meaning, here I’m going to treat its geometry as meaningful. And in advance: I have carefully chosen where to place my pieces on this board to give the result I want. If you don’t find that convincing, I will not be convincing you today.

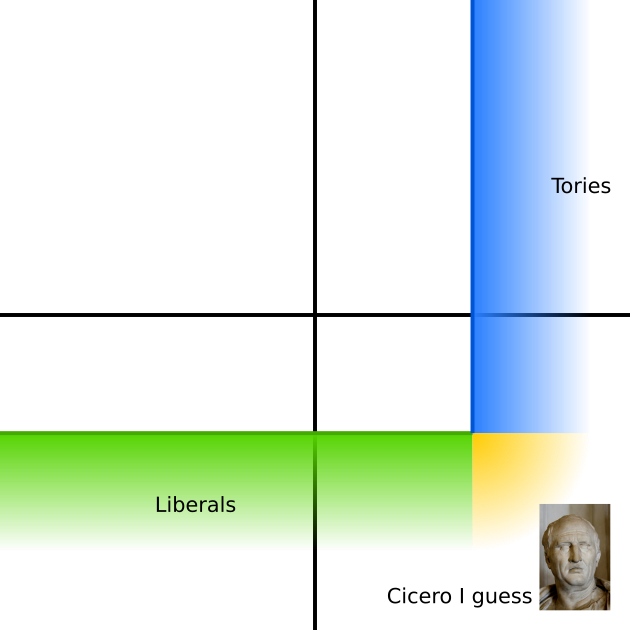

Let’s start with the ruling class. These people spend four years at Oxbridge studying Cicero or whatever, and when they emerge they’ve come to one of two political conclusions. Being ruling class means being able to do whatever you want, so some of them become Liberals. And being ruling class also means being rich, so some of them become Capitalists. These two groups of ruling class ideologues form political parties.

We’ll model each of these as being in a cloud occupying one side of the spectrum. As it happens, their concerns are focused on completely different axes. We imagine that each of them has a bright line on their preferred axis. The point of making a party is to create a common position somewhere on that line, win power, and thus force society in the preferred direction. If a party compromises beyond that line, what’s even the point of paying a membership fee?

Now, being ruling class rather more strongly involves being rich than being able to do what you want. So the convictions of the Capitalists are rather stronger than those of the Liberals, and their bright line is further from the centre. This is one of the most important asymmetries in this argument.

The two parties swap the reins of power back and forth. Liberals pass Liberal laws and repeal Capitalist laws. Capitalists pass Capitalist laws and repeal Liberal laws. The laws that remain in the long term occupy some corner of consensus in the bottom right. These are the principles internalised by the civil service, and they gradually form the bedrock of civil society.

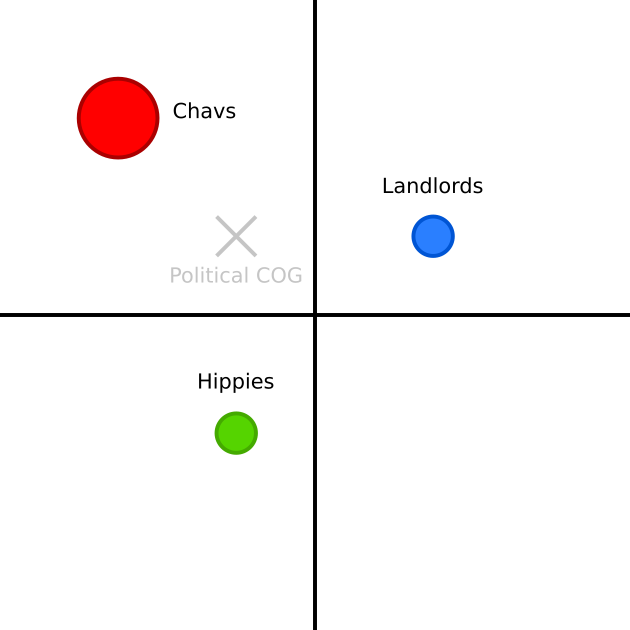

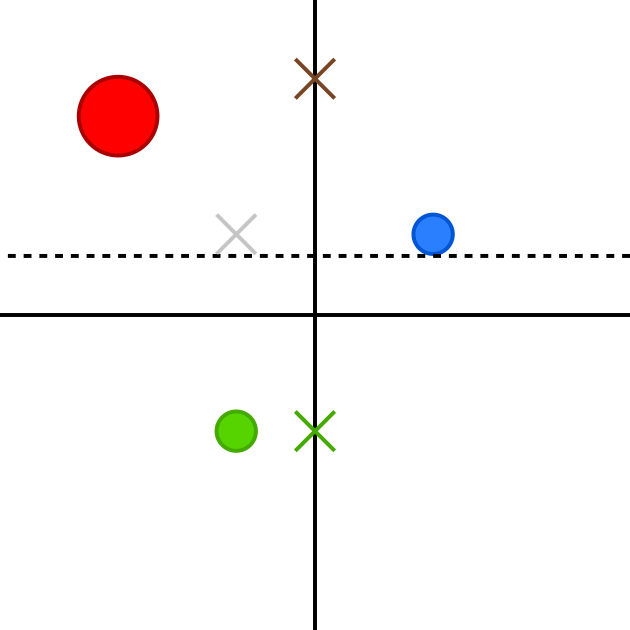

Now we come to the ruled classes. I’m modelling these as three entirely distinct groups. There is the base of the Liberal party and the base of the Capitalist party. These are numerous enough to be significant. The third group is the traditional working class. Unsurprisingly, they are the opposite of the ruling class in every way: illiberal and anti-capitalist. They are also more numerous. This is the other decisive asymmetry in the system. Somewhere between all three groups is a political centre of gravity, although that’s the opinion of no-one. Notice that no-one at all is in the lower right quadrant.

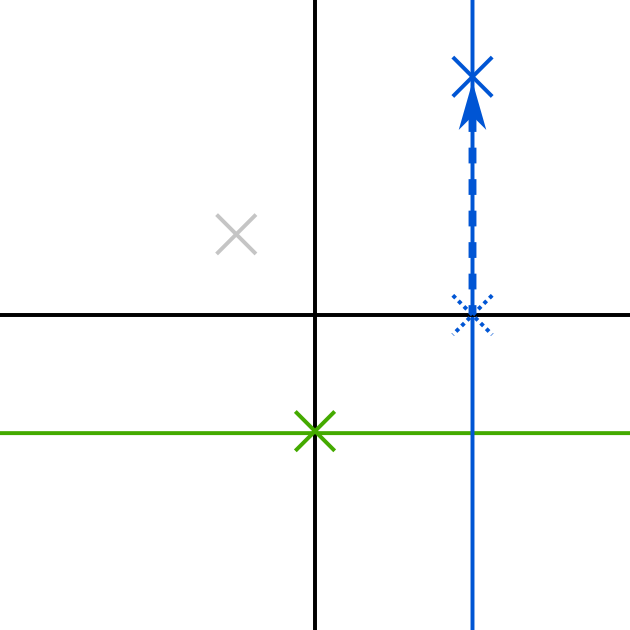

It’s election time. The two parties choose a position. Obviously that position is on their respective bright line: any more extreme and they’ll lose votes, any less extreme and their members would reject it. That takes care of the position on one axis. The position on the other axes is entirely flexible. Let’s just choose a position in the centre for each party.

What’s the result? We can draw a line exactly midway between the two parties’ positions. Everyone compromises between the two axes of opinions and votes according to which side of the line on which they lie. The bases of the two parties are balanced. The deciding vote in this case is the working class. The Capitalist party is more extreme. This bends the line towards the vertical, effectively making economic policy the deciding factor. Thus, the Liberals win the working class vote, and the election.

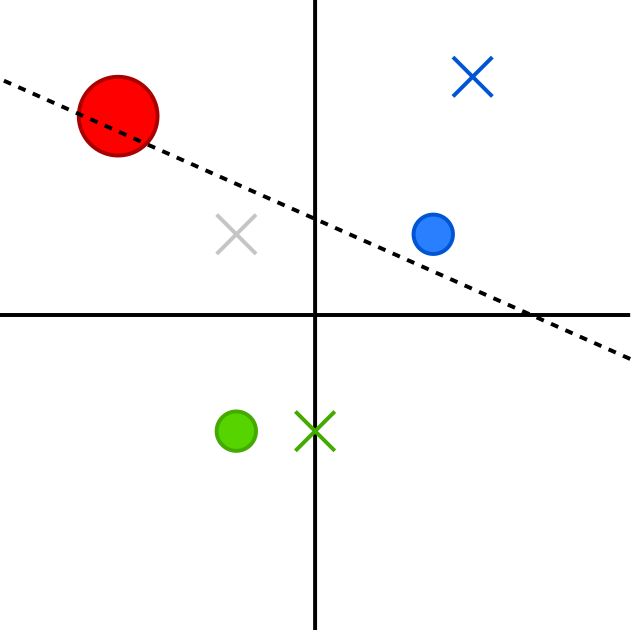

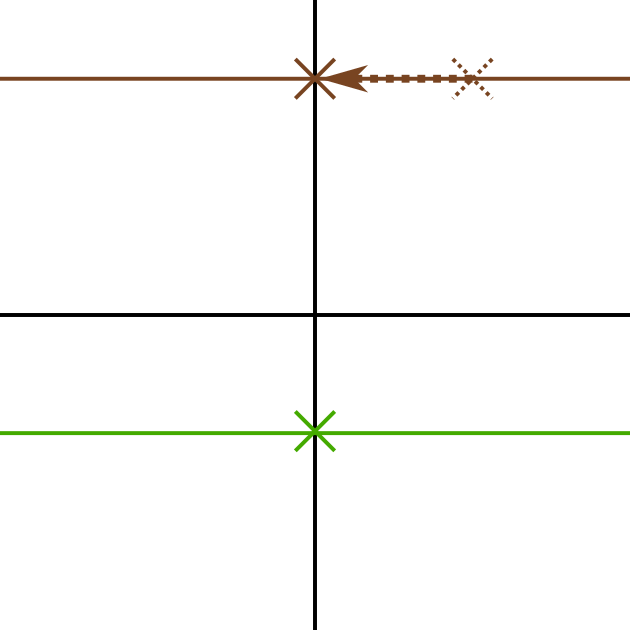

How can the Capitalists regain their competitiveness? The obvious thing is move left, but their membership won’t allow it. They could become more Liberal, but what’s the point? The Liberals will always appeal more to Liberal voters. No, they move in the opposite direction, becoming more socially conservative.

The new position is even further from the political centre. How could they possibly win the election? Answer: what they’ve done is tilted the dividing line towards the social dimension. They’re still on the economic right, but now their social position is enough to win over most working class voters. Even though the political centre of gravity still belongs to the Liberals, no voters actually live there. It doesn’t matter.

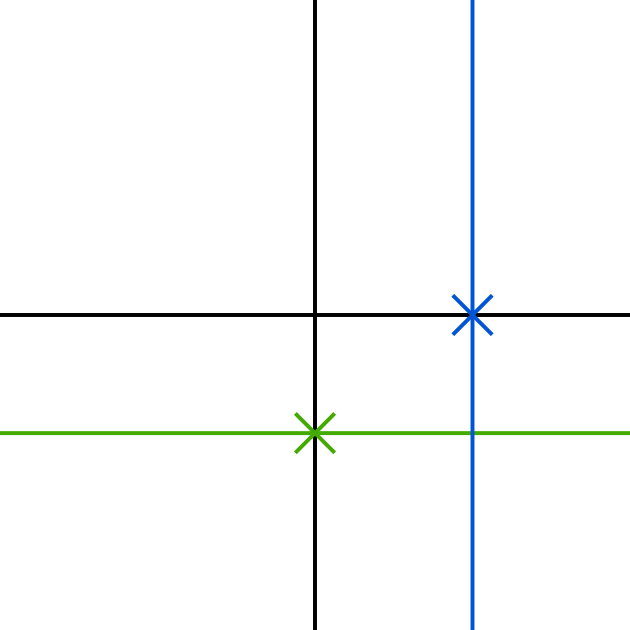

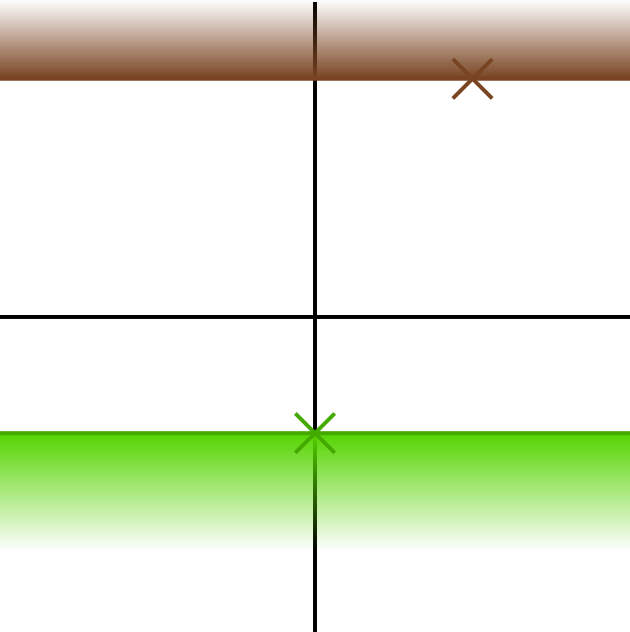

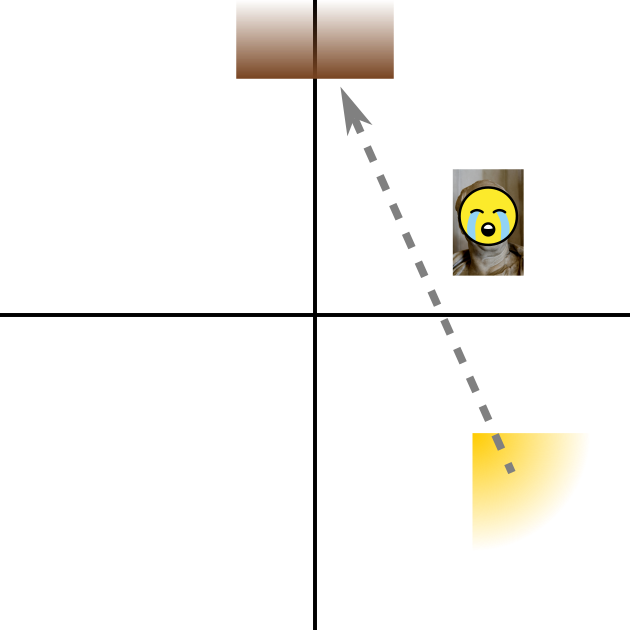

This is a great political strategy. But the Capitalist party has now taken on an existential risk. They’ve allowed themselves to be defined no longer as a political position on the economic dimension, but rather the social dimension. They are now the authoritarian party. This encourages a whole new crowd of members to join who have an entirely different ideological bright line. It’s not the Capitalist party at all any more: it’s the Authoritarian party.

Having taken over the party, why not complete the job? The old Capitalist bright line is no longer important. The party is free to move along the new bright line to adopt an extreme Authoritarian position at the centre of the economic spectrum.

Time for the next election. And it’s not even close. The political question is purely authoritarian or liberal. And both the Capitalist base and the working class vote for authoritarianism.

At this point, needless to say, it’s game over. There will not be any more elections past this point.

Taking a longer-term view, there has been a real political earthquake here. Civil society has been used to bouncing around a very narrow set of policies, far away from the actual opinion of the people, down in the bottom right hand corner. Over decades, the assumption of liberal capitalism has been built into institution layered upon institution. But in a few years, suddenly, a new durable political consensus has been established around an extreme anti-liberal position. It’s important to realise that this is not “political polarisation”. This is an irreversible revolution.

The best way to escape this trap is not to fall into it in the first place. And the way to do that, is to establish the principle that democracy is exclusively for democrats. If that’s not you, go fuck yourself.