Why, then, should we worry about declining numbers of people? Well, what reasons does the NYT piece provide? The argument could be a lot more direct. But the key suggestion seems to be that larger populations generate more innovation, and hence more (per capita) economic growth. That, of course, will hardly persuade people who think more growth is something we can ill afford on a limited planet. We’re also, obviously, owed an account of why less growth would necessarily mean lower levels of well-being. But it seems the idea is simply that fewer people means fewer Mozarts, fewer Marie Curies, fewer Henry Fords.

What if there were far fewer people? by Chris Armstrong on January 8, 2024

I posted a comment under that post. I made an attempt to compress my point into something both short and persuasive, and comprehensively failed on both counts. So, to the blog!

Technological Stagnation

The reason I’m coming back to this today is another Crooked Timber post

American culture is premised on progress. This culture has delivered, when it comes to technological progress—though far more in terms of bits than atoms, of late, and recent “AI” trends seem likely to further exacerbate this gap.

I’ve been hearing this cliche, that technological progress is “dizzying”, my entire life. And it’s been an empty promise my entire life. It’s a boomer cliche, nothing more. People who grew up in the 60s really did live in an era of omnipresent improvement, among elders who also grew up among omnipresent improvement.

But when I studied Computer Science, the references all came from the 60s. Whatever technological marvels I personally experienced (I enjoyed playing with the then-exciting field of computer-generated imagery), the core algorithms were all set in stone decades before I even started. The only difference between my coursework in the 90s and my professional life today is that those algorithms are literally standardised and then buried, such that I never need to think about them. New recruits don’t learn algorithms at all.

In fact my professional work is conducted mostly through Emacs running on Unix, an environment completely familiar to a technologist from the late 70s. Emacs is written in Lisp, a programming language from the 50s still far superior to the hundreds of new languages invented every year. And of course, I’m writing this article in Emacs too.

So what did we achieve in 60 years of innovation? The iPhone, obviously. And innovation in computer chips does seem undeniable. But this is entirely swallowed by Wirth’s Law. It’s been commented that the Chinese were first to invent paper and gunpowder, but used them to make kites and fireworks. Well, kites and fireworks are cool. We use chips to put imaginary cat ears on our heads during video calls.

But what else? The truly important change is renewable energy. But the world still burns more fossil fuels each year then the year before. If there’s any social change resulting from this, I can’t see it. Appliances from 60 years ago plug into the same socket in the wall. Primary school kids are not taught differently.

What about social networking? That’s social change isn’t it? Maaaybe. Get a historian in the room to talk about chapbooks and pamphlets to test that argument. More importantly though: social networking does not require any new technology. Trolls, spam, blocking, moderation, feeds, filtering: these are terms from Usenet. The scale isn’t even any larger: there may have been fewer connected people in the Usenet days, but they were all on one system. Now the teeming millions are splintered into tiny inbred communities like Twitter. Either way, we’ve long had all the sociological tools we need to study social media.

It’s been many generations since society was forever altered by anything on the scale of steam engines, or railways, or the telegraph, or radio.

The true innovation of the last 50 years wasn’t technological at all: the privatisation of our civilisational accomplishments into the hands of a tiny number of kleptocrats. It’s at least symbolic that the traditional econometric marker of “innovation” is the number of new patents. Measuring innovation by counting patents is like measuring population growth by counting fresh graves. There have indeed been a lot of fresh graves recently, but I’m far from convinced that means what you think it means.

Liberalism

I’ll link to an irritating article from Nate Silver just because it’s the most recent working definition of liberalism in my browser history:

To simplify: liberalism is a political philosophy that’s centered around individual rights, equality, the rule of law, democracy, and free-market economics.

This is, at least among the global elite, the dominant and unquestioned basis of all social organisation.

Why?

The alternative to liberalism is traditionalism. To set these against each other, liberalism stresses trying things out for yourself, starting from first principles, using your own experience coupled with strong analytical skills to guide your judgement. Traditionalism stresses listening to people who have gone before you, and copying their successful actions.

Surely it’s obvious that traditionalism is the far superior strategy. Having to rethink the entire basis of your life from scratch is absurdly difficult, and you’re bound to make catastrophic mistakes. Whereas following the advice of elders, preferably those whose interest is using you to carry forward their genes, seems practically foolproof.

So why did liberalism develop such an entrenched position among the founding principles of our institutions? Even when the institutions themselves would clearly be served so much better if people simply obeyed them as authorities?

The answer is that liberalism is evolutionarily adaptive in a world of constant change. In a world of bucolic stasis, societies that lose track of their traditions quickly expire. But once the industrial revolution, with its research laboratories and capital markets, rolled over the social landscape, traditionalism became nothing but a hindrance. Attempting to take up your father’s trade is a recipe for financial ruin, when every trade is made redundant by hitherto unimagined new trades within a generation.

Liberalism is nothing more or less than the institution of adaptability. And since the most adaptable period of a human’s life is infancy, liberalism is characterised by neoteny. We act childish, and learn to be proud of our childishness.

As proudly childish people, we invent myths. Galileo defied the authorities, insisting “and yet it moves”. And so we have <gestures wildly> all of this.

But perhaps it runs the other way? Change came first. Continual change produced death and destruction and misery for centuries. Eventually, liberalism emerged as an adaptation to change, a way to thrive not merely despite continual turmoil, but as a way to exploit it.

What Causes Change?

I got this answer to the question when I asked John Quiggin:

The main engine of change is technological progress, not growth in inputs of labour and resources.

But this is begging the question. What causes technological progress? I think there are three models.

Serendipity

In any given year, a certain proportion of people will fall asleep under apple trees. A certain proportion of those trees will drop apples. A certain proportion of those apples will hit the sleepers’ heads. And presto, ideas are born!

Hooking this back into the topic at hand, how does this relate to population? The answer is, more people, proportionally more ideas. One in a billion people are Mozart. With 8 billion people we have 8 Mozarts. Eight! That’s, like, 7 more than anyone else had! And if we let the population slip to 4 billion, we’d only have 4. A mere four! What even would be the point of a civilisation that can only afford 4 Mozarts?

Enlightenment

Or, maybe technological progress is itself a technology. Woah. Mind blown. Now that we know how to do technological progress, which requires universities and multinational corporations and aeron chairs, we never need to re-learn that idea. Even if the population is reduced to a theoretical end-times Adam and Eve, Eve will spend her evenings slumped over her chardonnay waiting for Adam to finish pitching his latest crypto startup. So really, worrying about population decrease is just silly.

Change

But there’s this third model in my head. Perhaps the driver of technological progress is change. If your life is static, if you can happily make a living the same way your parents made a living, why would you even bother coming up with new ideas? That sounds hard.

But when you’re made redundant because AI chatbots can do your job cheaper than you can, you’ve gotta come up with a plan B. And that’s also a story that sounds extremely familiar. Necessity is the mother of invention. In the absence of change, where do we get the necessity?

But if change is caused by technological progress, and technological progress is caused by change… then technological progress is not the engine after all. Technological progress is static mass on the flywheel. Sure, that’s where the momentum lives. But that momentum is only recycled. The original source of the momentum must be somewhere else.

Stocks and Flows

The mathematical difference between my three models is how the rate of change relates to the population size. Serendipity produces change proportional to population. Enlightenment produces fixed change irrespective of population. And Change? That produces a feedback loop proportional to the rate of change of population. The final rate of change is multiplied many times over the initial rate of population increase.

There’s a society with a static population that lives in houses. Houses last 100 years on average. Each year 1% of the housing stock must be replaced. Building is a venerable and respected profession.

Now the population increases 1% per year. Annual new builds rise to 2% of the housing stock. There is twice as much building, but that itself presents new opportunities. Construction technologist is a whole new profession. Every year, new techniques, new economies of scale, are invented. Ordinary builders can no longer just do an apprenticeship and work for life, they’re expected to keep up with industry trends.

Now instead the population decreases by 1% per year. There’s no need to build new houses at all. When a house falls down, the occupants just move into a vacant one. The skills of housebuilding fall into disuse and are forgotten. Centuries later, people gaze in awe at the glorious monuments of the ancients, marvelling at their lost wisdom.

Friction

So here we are in our liberal society where childishness is a virtue and no-one knows anything and it’s not worth remembering which button on your remote control changes channel on the TV because it’ll just be replaced with an app tomorrow and in the meantime you can ask Alexa. How are we all faring?

We all hate it.

We literally did not evolve to work like this. We like being told the rules and following the rules. We like having someone who will tell us how to do everything. We feel comforted by the pull of the leash. We look to the people around us to guide our decisions, and resent being pushed around by unreasonable machines and bureaucracies.

Liberalism is just stupid. It’s no way to run your life. It hurts and it sucks and I shouldn’t have to.

The only reason people would even consider Liberalism as a social strategy is if there was absolutely no other choice available. Only a population riven for centuries by continual change, plagued by, well, plague, and war and famine and unemployment and overwork and so on, would consider adopting Liberalism as a way of keeping their heads above the waves. But that population will be constantly looking for an escape route out of Liberalism and back to healthy, predictable, traditionalism.

Some more than others. What I’m saying is, lots of people vote for Donald Trump. Those people are pushing hard against the flywheel to make it stop.

If you like Liberalism, you can’t just rely on the cycle of technological progress to keep spinning on its own. You need to be pushing forwards with at least the strength of the people who are pushing back in the other direction.

Population Growth As Engine

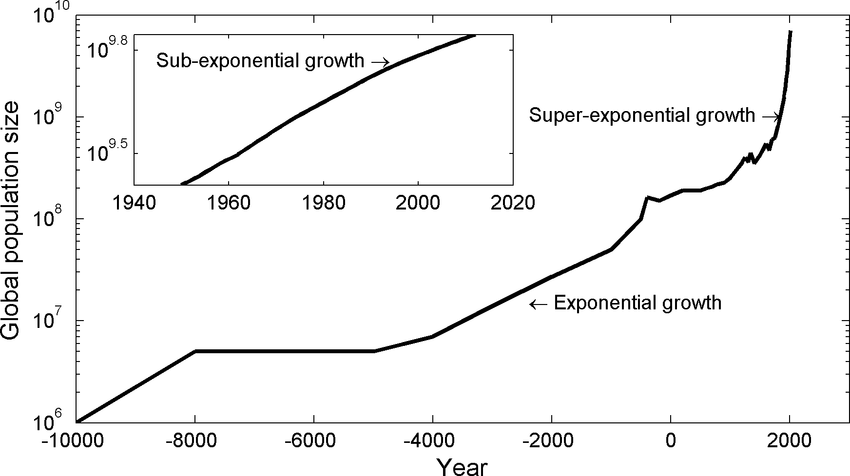

Here’s a fairly typical graph of population over the long term.

According to this, population has been exponentially growing, with minor interruptions, since 4000 BC. But the 20th Century was a whole different regime of crazy population growth. And now, in the 21st Century, that regime is over. We are now seeing a slowdown, and probable stagnation, for the first time in several millennia.

If you don’t think that that’s, like, a thing worth noting, you’re crazy.

I have several models of how population drives technological innovation, which drives change, which is the raison d’être of Liberalism. But at least one of those suggests that we are about to kick out the scaffolding that holds up our entire civilisation. I feel like that warrants some analysis.

Will Liberalism persist? That is definitely a maybe. We’ve never tried running Liberalism without a regime of both population growth and increasingly intensive resource extraction. It seems like a good idea anyway. But Liberalism has often seemed like a good idea in the past and failed disastrously.

The Tipping Point

Meanwhile, it really feels that Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin and Xi Jin Ping and Marine Le Pen are shaping the world in ways that wouldn’t have been possible when I was growing up. Everyone always gripes about kids these days. But from where I sit, borders are slamming closed, politicians reminisce about imaginary golden ages, technology is distressingly stagnant, wealth is becoming more concentrated, freedoms are becoming more limited, and kids don’t drink, don’t do drugs, study hard, save their money, and have no hope of achieving my standard of living in their lifetimes.

Could it be that we’re already past the tipping point? Population growth has been slowing for a generation now. Rich countries have fertility rates far below replacement, and poor countries are emulating that demographic shift. You’d expect the flywheel to keep spinning some time after the engine sputters out. Are we already seeing what happens when the reactionary forces have the upper hand?

Climate Change

Surely the biggest problem with population growth is the urgent need to reduce carbon emissions. It is obvious that half as many people would release half as much carbon dioxide, all else being equal. Forget ideology and philosophical musings, our survival is at stake here.

The problem with that argument is that the need is, like, really really urgent. This decade urgent. Reducing population by a significant amount in that time would require… a fairly dark turn. Let’s not go there. Conversely, the difference between the status quo and actually encouraging people to have children, say by ubiquitous free child care and compulsory multi-year parental leave for both parents, would not have any noticeable effect on carbon emissions over the timescales we’re talking about.

So, while environmental damage is probably the most important counterargument to all of this, and one I completely sympathise with, I’m including this section only to note that it is entirely a red herring.

What to do

So, am I a pro-natalist? Hell no.

Ultimately, that cannot possibly have a future. We may still get over the current environmental crisis. But exponential growth cannot continue forever.

Certainly I can’t go around being a pro-natalist without actually having any children. God knows I’m not going through that just to back up a blog entry.

Instead, I’d like to see a re-evaluation of the principles we’ve accepted until now. To what extent is continual growth an unspoken assumption? What liberal principles survive a transition to a degrowth world, and which principles do not? All my life I have been explicitly and implicitly taught to think for myself and reject conformity. Some of that doesn’t make sense in the 21st century. I would very much like a heads-up which bits I should let go.

See, without that, the alternative is TESCREAL. We can’t exponentially burn resources on Earth, but there are centuries of exponential growth waiting for us off-world. It’s a shame about the pandas or whatever, but if my choices are a Bishop ring or authoritarianism, why shouldn’t I sign SpaceX’s contract?